Pandora was given a beautiful container which she was not to open under any circumstance. Impelled by her curiosity given to her by the gods, Pandora opened it, and all evil contained therein escaped and spread over the earth. She hastened to close the container, but the whole contents had escaped, except for one thing that lay at the bottom, which was the angel of Hope named Astrea.

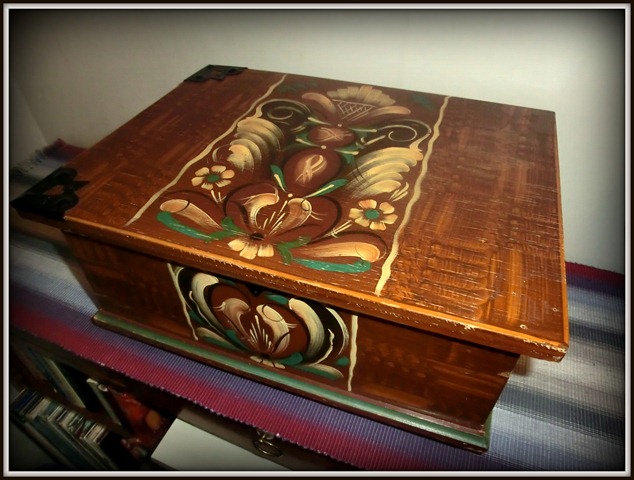

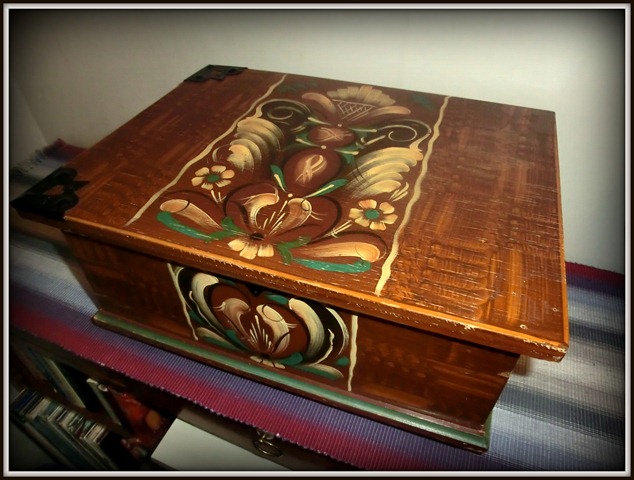

No, this is not really Pandora’s box – it’s a small treasure chest that belonged to my grandmother Sally. This was one of the first objects I took home with me from the House after my father died last summer, knowing it to hold some old notebooks and other memorabilia. Until now, however, I haven’t really looked at the contents more than to establish that yes, there were the notebooks, and some various old letters and cards and press cuttings and such.

But as this week I’ve been getting on with the old postcards, I decided to take a closer look at the letters in that chest to see if there were any that related to the same period as the postcards. I found some more postcards of later date than those in the albums, but only two letters written by my grandmother’s sisters.

Most of the letters kept seem to be correspondence between my grandparents in the late 1920’s, before their marriage. (Which may still hold secrets to be revealed – I have not yet read them.)

However, I also found some other documents I did not know were there, and those are what inspired this post.

I’ve known since early on in life that my grandfather’s mother and uncle both ended their days in a mental hospital. It was not a secret, but also not much talked about. In later years, I understood from my father that back in his childhood and youth too, these things had only been talked of “in a hushed voice”. My grandfather Gustaf was born “out of wedlock” and was raised primarily by his grandparents, while his mother was in mental hospital.

After my dad died last year, I found two files with notes on family history collected by him and his father before him. I was struck by the fact that while my grandfather had dug deeper into the history of earlier generations than I had been aware of, I found no mention of his own mother among those notes. I assumed he might have found that to come a bit too “close”. (I only need to look at myself now to understand that… I’m finding it a lot easier to dig into the history of my grandparents’ generation just now, rather than my own parents who only recently died.)

While trying to lay the puzzle of what I know and don’t know, I have wondered sometimes what kind of mental illness(es) it was that my grandfather’s mother and her brother suffered from; and if it might perhaps be possible to track down some old hospital records to find out a bit more - some time. (It’s not exactly been at the top of my priority list.)

However – I just found out I’m already in possession of more information than I was aware of. In that old chest, there was a scroll of rolled-up old letters, which I’d not properly examined before. When I sat down to sort these out, I realised that besides two or three written by Gerda to her parents – not really saying very much – the rest were official reports from the mental hospital sent to her parents.

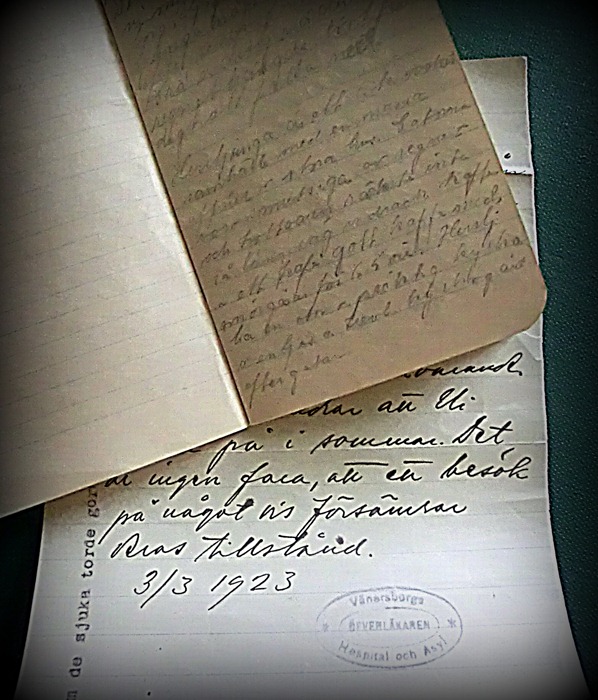

Moreover, among the notebooks, I found one which contained my grandfather’s very detailed account of his impressions and thoughts from when he, in 1923, a week before his 19th birthday, for the first time went to visit his mother at the mental hospital Restad in Vänersborg; accompanied by his grandfather (the grandmother having died the year before). He also went there again on his own the following year, and made notes then as well.

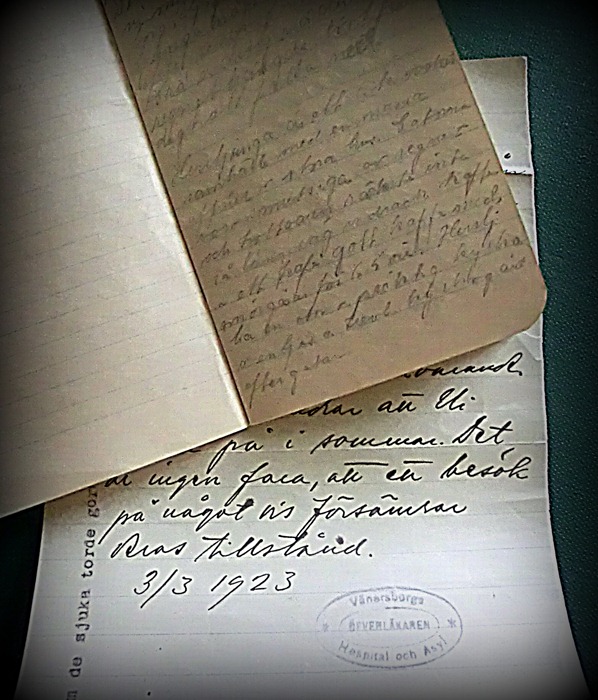

“There is no risk that a visit could in any way make their condition worse.” 3/3 1923 – stamped by the chief physician at Vänersborg’s Hospital and Asylum.

My grandfather’s notebook on top. It’s written in such tiny handwriting that I had to use a big magnifying glass to be able to read it.

While there is no specific diagnosis mentioned in any of these documents, the official reports state that Gerda was suffering from visual and audio hallucinations, was often aggressive but also passive and uninterested and mostly staying in bed. She seems to have grown worse over the years and at no time do the staff express any hope of her getting better.

The few letters which she wrote herself to her parents and her son are from the earlier years. The first report and letter are from January 1919. This could mean she was first admitted to the hospital in 1918, when she was 40 and my grandfather Gustaf 14.

From Gustaf’s notebook it seems there was a time in his childhood when his mother was living at home and working at factory in the village (he was trying to find out when visiting her at the hospital, if she still remembered those days too).

Her brother was committed to the same mental hospital already back in 1909 or earlier.

The hospital had separate wards for men and women, and the brother and sister seem not to have been in contact with each other. All the official reports include notes on both of them, though. On each report there is a typed line that says: “Enquiries about patients should be made by letter, not telephone, and must include return postage.” The actual reports, however, are all written by hand.

The brother was obviously physically strong and usually spent his days doing outdoors work; but is said to be performing his tasks “like an automaton”. (I was a bit surprised to find that word used in psychiatric context back in the early 1920s.) He suffered from strange delusions and kept talking nonsense about wars and of going hunting for exotic animals like elephants and tigers. His condition seems to have remained more or less unchanged through the years.

I went searching on the internet for some facts about the place. The Hospital/Asylum at Restad was built between 1900-1905. It was a huge institution which housed over 1000 patients, long-term and short-term. Back then it was a very modern facility for its time, situated near the river and surrounded by a big park.

It was a self-supporting community. They grew their own crops, kept their own livestock, cooked their own food, baked their own bread; there were workshops for carpentry, paintwork, tailoring, shoemaking and whatever. They had their own water tower and electricity and even their own tram system for transportation of food and washing. (You can see the tracks in the photo above, I think.)

What I have not been able to find out on the internet is what kind of treatments they gave the patients back in those early days, except trying to keep them occupied!

Gerda seems to mostly have talked of the nurses as being kind, and had no complaints about how she was treated, except perhaps for one remark that her son makes note of on his second visit in 1924: “The other day they had put Gerda on a table and held her there. ‘I suppose they were angry with me,’ she said.”

For young Gustaf it was obviously a heartwrenching experience to visit his mother in this environment, among a lot of other mentally ill people.

Between 1906 and 1957, nearly 2000 people were buried in the hospital’s own cemetery, most of them anonymously, their crosses only marked as male or female. In 2009, a memorial was raised to honour them all posthumously:

My grandfather seems to have arranged for a proper gravestone for his mother though (she died in 1933); and later when her brother died (in 1956), his name too was included on that headstone.

While Gerda spent perhaps about 15 years in this institution, her brother lived there for 47 years or more.

From Wikipedia I learn that the first antipsychotic drugs weren’t discovered until in the 1950’s. When they were introduced, they revolutionized psychiatric treatment.

In 1989, most of the psychiatric care (I assume a lesser number of hospitalised patients by then) was moved from Restad to a new general hospital.

Currently, the old Asylum area is being turned into a modern housing estate with the old buildings now used for hotels and businesses and cultural activites etc.

In 2011, a brand new unit for psychiatric care was built quite close to the old one. This will take 82 patients, with 54 of those places set aside for forensic psychiatry. (Compare that to 1080 back in the early 1900s.)

The first three photos in this post are my own;

the rest I found at nyheter.vgregion.se,

www.restadgard.se and www.nusjukvarden.se